|

Ecological flow, nature protection, and the wolf |

||

|

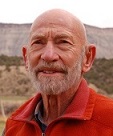

Michael Soulé |

Richard Mabey observed in his biography of Gilbert White (1720-93) that White’s book The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne was as much about the village life and the people of Selbourne, as it was the natural history of its setting (1). Mabey was wary of the iconic status of the book until he visited Selborne in Hampshire and saw those settings for himself, conjecturing that the landscape had changed little from the eighteenth century when White had made his observations of its natural history, particularly on the first appearances in the year of different animals, birds, and plants; the soils, climate, trees and management of the landscape; but also the dates of crop harvests, as well as the day to day village life of domestic animals and livestock, jam making and vegetable growing. White wrote to two other naturalists about the natural history in letters that spanned a couple of decades. He would catalogue the human history of Selbourne as a settlement in a series of letters on The Antiquities of Selborne, that were not intended for posting, letter writing having become his means to record his scholarship, and which were also included when his brother Benjamin drew all the letters together and published the book in 1789. Gilbert White saw in the letters his “idea of parochial history” that he thought “ought to consist of natural productions and occurrences as well as antiquities”(2).

I grew up on the south coast of Hampshire being

educated in its county notables like White and novelist Jane Austen. Places

like Selborne, and the nearby Chawton where Austen lived, were part of the

sparsely populated areas to the north of me, a vast, inaccessible private

rural landscape dominated by agriculture. I have to say that decades after

leaving Hampshire, when I eventually went for a walk along the lanes and paths

amongst the low hills around Selborne, passing the bands of woodland, and

following routes that were assumed to be those of White, all I saw was that

landscape of parochial history, the planned landscape of field

enclosures, the managed hanger woodlands on steep hillslopes that are

marked ancient (3) but seemingly empty, at least the sections I saw, and a

tamed stream. I’m sure if I walked there every day, and over the seasons,

I would build up a list of sightings of species commonplace in such

parochial landscapes, only there by way of cultural forbearance. However,

I reference White now for something that even Richard Mabey didn’t pick up on

in his biography, that White had a sense of the natural world of Selborne that

predated its possible settlement by early Britons. Thus White sets the scene

in the opening sentences of Letter I in the Antiquities of Selborne (2): A high point of 210m (689ft) for Selborne Hill hardly makes this a mountainous district. Setting aside whether this landscape was early settled by returning hunter-gatherers in the post-glacial landscapes of the Holocene (4) it is an easy assumption that it was home to wolves and bears that fetched up 13-9,900 years ago after a postglacial recolonisation of Britain from southern refugia (5). I’ve written before about the persecution of wolves when they posed a threat to the systemised exploitation of land brought in by the Norman Conquest after its wholesale expropriation for deer hunting, as they were also a threat to the organised sheep grazing of the Abbeys, who made fortunes selling wool in Europe (6). Wolves were still regarded as common in many areas during the reign of Edward I (1272-1307) but in 1281 the King ordered their extermination, a campaign that was largely successful (7,8). However, people continued to hold land and commissions dependent on the destruction of wolves, a clear indication that the fate of wild nature was continuing to be dictated by power and ownership structures. By the time of Henry VII (1485-1509) wolves were extinct in England, and it is unlikely that White would have been much aware of their continued but perilous existence up until the mid-eighteenth century in Scotland, a period that overlapped with his early life. As a keen observer, would White have seen the absence of wolves around Selborne as a nature deficit, or have been concerned or even cognisant of the depauperate state of what wild nature there was? Would he have seen any value in the reinstatement of wolves to the landscape of Selborne, considering that he wrote about his sightings of deer and their life history so that they and the hanger woodlands offered prey and den sites for the wolves, or would he have considered it too disruptive of the parochial history of Selborne’s landscape? While various observations in White’s natural history could suggest an early stirring of ecological thought, his level of understanding of natural trophic processes was formed many years before our current knowledge of food webs, trophic levels, and the importance of large carnivores (9). I would like to think, though, that if I were to speak to him now, he would be fascinated by the advances in knowledge of animal-plant interaction, and would be keen to see it in person. I would explain to him that we have learnt so much more about how impoverished of wild nature our landscapes have become. I would hope that he would take me to task, that knowing all this, why had we not done something about it? I would have to say that it was partly his fault; that his excelling at natural history became a convenient but typical British panacea, substituting the radical and challenging need there was to reverse and protect against the wholesale simplification of our landscapes. I would say we needed to stop seeing wild nature as the acceptable backdrop to our parochial history that we can dip in to and out of observing, but instead should be the foreground in its own space and where our presence is an inconstant feature. I would tell White that our approach to nature conservation, the protection we give to wild nature against our domination is totally inadequate; that it has no spatial aspect in terms that provides an autonomous space of strict protection for all species; it is limited in its range of species protected because it is compromised by acceptance of pest control; it is riddled with exceptions; it is routinely transgressed as enforcement and penalties are ineffective (10); that there was nothing on the horizon that suggested this would change; that the only way that we can break out of this is the radical action in facing up to the challenge of reinstating the wolf and learn how to live with it. So much else would follow that action. The crushingly poor outlook for wild nature I briefly reported last November on the shortcomings of the Environment Bill before it fell because of the General Election (11). The Bill returned to the Commons last January with little alteration, reaching Committee Stage after Second Reading (12,13) but is now postponed from moving further through the legislative process until probably September because of the pandemic-induced anthropause (14,15). I have already noted there isn't even any mention of the National Nature Recovery Network in the Bill when this is the key aspect of the 25 year Environment Plan (16) and is what the Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS) of the Bill are supposed to feed in to; that there is only a vague and uncommitted nod to public participation in drawing up LNRS; and that there is no attempt to create new designated protected area types, particularly strictly protected areas, for any newly identified opportunities for nature recovery in LNRS (11). Indeed, written evidence submitted to the Public Bill Committee examining the Bill from a self-absorbed group that styled itself “49 Club” vehemently opposed any such change (17). The Club formed in 1991 is an association of over 200 former staff of the statutory nature conservation agencies that took its name from the year 1949 when the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act became law, and which declared the deeply flawed designation of Sites of Special Scientific Interest that tied nature conservation to agriculture (18). Moreover, there isn't even any decent language in the Bill that relates to the ecological function of networks, although there is an amendment that was proposed during Committee Stage to rectify this (19) but it only introduces an element of ecological coherence in terms of sites in a national habitat network (see later) rather than talk about a coherent ecological network that facilitates wildlife refugia and movement. My prejudice suggests that wittingly or not, this approach to ecological networks is more concerned with ensuring land use rather than maintaining or restoring ecological functions as a means to conserve biological diversity (see 20,21). I keep finding out more depressing things about the context of this Bill, but again it seems pointless to enter into a full critique until the final damage of lost opportunity can be seen when it becomes law. However, I will mention the National Natural Capital Atlas that allegedly maps the state of our natural capital based on eight broad habitat types, and in terms of its quantity, quality and location. It deals in "Ecosystem Logic Chains" that sees an “Ecosystem Asset” producing an “Ecosystem Service” that provides a human “Benefit” and therefore has “Value” (22). Proximity and accessibility of habitats to people are not assessed other than by Rights of Way. There is no indication of whether the quantity and spatial distribution of these "natural assets" provides any benefit to wild nature. There is also the National Habitat Network Map, a requirement in the Environment Bill, to inform production of the Nature Recovery Network of the 25 Year Environmental Plan (13,16). It is based on broad habitats, mostly the priority habitats required to be identified under Section 41 of the NERC Act 2006 (23-26). Allegedly, this mapping is supposed to be supportive of the development of the LNRS, but there is no indication that the spatial distribution of these habitats provides any benefit to wild nature in supporting species life histories, refuge, movement ecology, and dispersal. I am deeply suspicious of this habitat network mapping, as it shows my house as being in a “Network Enhancement Zone 2” – land within close proximity to an existing primary habitat, presumably the moorland above me, but which is unlikely to be suitable for re-creation of that habitat, although it may be where other types of habitat may be created (the moor is BD17 5EE in (26)(27)). Could they be referring to my garden pond? Between my house and the moor is a horse field that is marked as “Network Enhancement Zone 1” - land within close proximity to an existing "Primary Habitat" that could be restored to that habitat, and then the bulk of the moor is “Restorable Habitat” presumably as the primary habitat. The primary habitat is not revealed on the mapping for these Zones or Restorable Habitat, but there are two very small areas of heathland marked within the moor, one is Upland, the other is Lowland, and one day I may actually work out why these insignificant areas warrant the distinction, or even what marks them out to being any different than any other area on the moor. It is painfully obvious, though, that the “Restorable Habitat” is the area covered by the agri-environment agreement on the moor, itself a bogus vision that denies its true potential for wild nature (18,28,29). Natural England had, in advance of this National Habitat Network Map mapping, established a project within its organisation to bring national habitat and species specialists together to rationalise technical approaches to individual habitat types, species groups and priority species (30). The project was said to focus on “understanding how different habitat types function and relate to each other naturally in the landscape to provide the combination of structure and niches required to support native wildlife”. Discussions within this project highlighted tensions between cultural management regimes and associated management boundaries on the existing pattern of biodiversity in England, and how a cultural perspective could constrain perceptions of how habitats function naturally. It was recognised as a dichotomy between management philosophies based on accepting cultural landscapes as the reference point for biodiversity conservation – “species gardening” - compared to using natural processes as a reference point. Absolutely, and why the predominant characteristic of the National Habitat Map of inevitably cultural habitats is a poor starting point as an assumption for functional coherency of ecological networks. Even within a more natural landscape of woodland habitats, the dichotomy persists when cultural practice is slithered in as a convenient substitute for undertaking the greater challenge of fully restoring woodland ecology so that its assemblages determine its functional process rather than us (31). There is also a Natural England handbook that aims to help the designers of nature networks by identifying the principles of network design, outlining some of the practical aspects of implementing a nature network plan, as well as describing the tools that are available to help in decision making (32). I am in two minds about this handbook. It has some good elements, like involving people from the earliest stages in planning and design, and in creating an overarching vision for the network; improving the permeability of the surrounding landscape for the movement of wildlife, as well as creating corridors of connecting habitat; and developing a number of Large Nature Areas (5-12,000 ha) that will provide centres from which “wildlife will brim over into the countryside”. It recommends considering nature networks from a species point of view, and provides an appendix on the ecological requirements of nature networks so that they support persistence and movement of species. It notes the different mobilities of species, their daily and seasonal routine and annual cycle, and the factors affecting dispersal, and gives some examples that mostly relate to habitat patch size for a few, mostly inconsequential species, rather than ecological flow – don’t expect there to have been any interest in the movement ecology of foxes, more persecuted as a pest than appreciated for its intrinsic value as being a significant mesopredator in the ecology of our wild nature. This constrained view is also evident in the brief synopsis of a range of map-based models and tools that it says can provide useful support for decision-making during the planning and implementation of nature networks. The problem is that most of those map-based methods referenced are solely about habitat creation or restoration in relation to those habitat patches, like the National Habitat Network Map and the National Natural Capital Atlas, and only one is based on assessing ecological flow. This is the least-cost approach that works by defining the habitat for a generic and not real focal species, and modelling the connectivity based on the species dispersal distance and the impact of the landscape matrix on species movement ((6) and see Appendix A4.3.1 in (32)). I am at a loss therefore to see a great value in this handbook, or even who it is directed at, given that it says nothing about LNRS where the involvement of people is essential but not guaranteed in the Environment Bill, and only refers to the Nature Recovery Network that will likely be entirely driven by Natural England. Devising systems for the protection of wild nature Michael Soulé, who sadly died recently (33,34) leaves an incomparable legacy of scholarship and guidance for the recovery of wild nature. In one of his visionary articles in Wild Earth in 1999, Soulé averred that the way to change land-use policy was to change public values by inspiring people with a positive vision (35). He saw that there were two keys to creating that alternative vision for protecting living Nature: the first was to have hope for the future of wild nature, and which would be born out from having the science and resources to secure that future. The other key gave the means to achieve the outcome of that hope, which was through the power of citizen engagement– it was to “cultivate a sense of participation and ownership in Nature protection through personal involvement in the development of regional wildlands networks. Participation is also educational, and the process can elevate the land-use debate and help everyone achieve deeper levels of understanding about ecological issues. People dislike the imposition of policies from above, but they will often support progressive change if they have some role in its formulation”. He believed that nothing less than an extensive network of wild areas devised through participatory grassroots processes would ensure the survival of full and robust wildlands and ecosystems. It would be a nurturing of networks of people to nurture networks of wildlands. I cannot stress enough his point about participation being educational, that people will learn about ecology by being actively involved in devising systems for its protection. I met Michael once over a couple of days in Ambleside in the Lake District where we were speaking at a conference at the University of Cumbria, and then meeting up the next day to talk about setting up a Task Force for Rewilding. He had a very dry sense of humour. It was his friendship with Erwin van Maanen, another member of the Task Force, which got him to come over from America for the Conference. Erwin and Michael had worked together in Romania in the early to mid-2000’s on turning Michael’s vision of promoting and protecting the wild nature of the Carpathians into a plan to safeguard its ecological network (36). The Vision Plan was inspired by the earlier Southern Rockies Wildlands Network Vision, one of a number of Wildlands Network Designs supported by The Wildlands Project (37) where the goal was the preservation and restoration of large, interconnected and relatively undisturbed ecosystems within the southern Rocky Mountains ecoregion of North America (38). Like the Southern Rockies vision plan, that for the Carpathians focused on large carnivores as umbrella species to safeguard natural wildness in the Carpathians and conserve a high portion of its biological and landscape diversity (39). Romania is fortunate in having extant populations of wolves, bears and lynx. Central to the Vision Plan was the ecological network map that was explicit about the geographic locations of ecologically sensitive and internationally important habitat areas, and also the permissible land uses in those areas. Furthermore, it provided a delineation of the required ecological infrastructure for wildlife, minimising barrier effects and landscape resistance to large carnivore movement, in order to "perpetuate viable animal populations in diverse natural ecological communities governed by important ecosystem dynamics". Before I met Michael, or even Erwin, I had used some of the figures from this Vision Plan for safeguarding the Romanian Carpathian ecological network during a talk that Steve and I gave during a symposium entitled Wilderness at the Edge of Survival in Europe that was part of the 3rd European Congress of Conservation Biology in Glasgow in September 2012 (40). Steve mostly talked about our Wilderness Quality Index maps of Europe. My section started with mapping frontiers, how the use of mapping identified trans-boundary networks of corridors for wildlife, and how the co-location of carnivores with many other species in need of protection in the Carpathian Mountains was evidence of their umbrella effect in inhabiting areas that characteristically also supported many other species. The process of developing the network map included a series of workshops, fieldwork, consulting experts and scanning the literature, as well as local knowledge and telemetry data from radio-collared wolves and lynx, and then modelling to identify the location of core areas and ecological linkages on the basis of large carnivore range requirements using least-cost-path-analysis. The latter was about the ecological flow of not just the large carnivores, but of all the other species that were capable of utilising the ecological linkages that facilitated the movement of those umbrella species. Flow in an ecological sense refers to the gradual movement of plant and animal populations across the landscape over time (41). Populations expand when they produce a surplus of juveniles and these colonize new habitat at a distance from their source point. Juvenile animals can walk, climb, fly, swim, glide, crawl or burrow their way into new locations, and plants have evolved a host of mechanisms for dispersing their propagules by taking advantage of wind, water, animals, and people. If the current habitat becomes unsuitable, but available suitable habitat exists nearby, the constant flow of dispersers helps ensure that the new habitat will be discovered and colonized. There are three commonly used spatial approaches to identify and plan for ecological flow enhanced by the connectivity of networks. The principal method is based on real, not generic, species used as focal species, a single or group of mammalian species representative of various aspects of regional diversity, and whose refuge and movement ecology is favoured by particular environmental variables in the landscape. This is the focal species approach of Wildland Network Designs where sets of focal species were carefully chosen and used as indicators to identify areas for elements of the Network Designs, such as core wild areas, compatible use areas and wildlife movement linkages (42). Through their choice, recognition was given to the vital role of keystone species and processes, especially ecologically effective populations of large carnivores, in the maintenance of ecological and evolutionary processes (37). The observation is that if suitable conditions are available to these carefully chosen species, the umbrella species, then many other species will be catered for. A very recent study for the European Environment Agency mapped connectivity and potential linkages for forest and woodland ecosystems across EU Member States as a contribution to building a coherent Trans-European Nature Network (see later)(43). The study used the distribution of focal species where forest and woodland was at least one of their preferred habitats. The focal species had to be present in two or more of the Member States, were transboundary in distribution, and had to be in need of connectivity. They were chosen from amongst mammal species protected under the EU Habitats Directive (see later) and included wolf, bear, lynx, pine marten, beaver, polecat, wildcat and wolverine (see Table 4 in (43)). The mapping was a resistance-surface-based connectivity approach that was optimized so that the minimum resistance value (equal to 1) was found when the landscape was covered by forest and woodland ecosystems. Resistance values increased when animal movements had to occur outside forest and woodland ecosystems (e.g. intensively managed croplands) up to a value of 1,000 for urban ecosystems (see Table 5 in (43)). Since the minimum size for core forest and woodland ecosystems in the modelling was set at larger than 3,500ha, an inconceivably large area in Britain, then you would not be surprised that Britain was a complete blank on the connectivity mapping (see Fig. 3 in (43)). Another approach is the species-agnostic modelling of landscape connectivity. Instead of focal species, this models large-scale connectivity maps based on quantifying the degree of unnaturalness in the landscapes that is caused by human modifications, as well as other ecological and geochemical processes (44). It’s an anthropogenic resistance grid - natural lands having the least resistance; agriculture, or modified lands having more resistance; and developed lands having the highest resistance (41). It is based on the assumption that natural terrestrial areas facilitate connectivity, and the higher the degree of human modification, the more the ecological flow is restricted. A third method is based on an analogy to a current passing through an electrical circuit. Circuit theory describes the movement of individuals through a landscape by considering all possible pathways between grid cells of a resistance surface (i.e. maps of human influence) (45-47). Each pathway can be interpreted as a current. Grid cells that are part of many pathways thus have a higher current density compared to grid cells that are part of fewer pathways. The cumulative current density map of all pathways can be interpreted as overall landscape connectivity. Human–wildlife conflicts and the structures of power and ownership The National Habitat Network Map, the National Nature Recovery Network, and the Local Nature Recovery Strategies are not about environmental variables that favour the movement of real focal species, they are not going to be tested on the basis of their functionality for wild nature, nor are they about naturalness – they are not about ecological flow. We would learn so much about what an ecological landscape means, what connectivity across a landscape means, if we began to think in terms of ecological flow. As I noted above, the chances of a fox being chosen as a focal species for understanding movement ecology of the largest extant mammalian carnivore we have is unlikely given that it has long been persecuted as an inconvenient pest (48-50). That the fox has an ecological existence depressingly only surfaced during studies into the ecological consequences of badger removal commissioned to assess what impact the badger culling would have (9). The fox has no legal protection, while the badger allegedly has under the Badger Act 1992, but that law has one of those incorrigible exceptions that allows the cull to go ahead to prevent the spread of disease (see section 10(2)(a) in (51)) even though it does not follow international ethical principles for wildlife control (52). The persecution of the fox and badger illustrate the barrier we have to ecological understanding because of the dominion of land users over wild nature, and which has to be broken. It is why we talk about nature conservation and not nature protection. We give little protection to wild nature, and when we do it is always deeply compromised by exceptions. This is all about power and ownership structures. Witness the issue of 39 licences in Scotland since the beaver was given strict protection, and which resulted in 87 being killed allegedly to minimise damage to Prime Agricultural Land (53). Stating the obvious, human–wildlife conflicts arise from human activities. Is it beyond us to change human behaviour and renounce lethal control? How about preventing or mitigating human–wildlife conflicts by altering human practices wherever possible and by developing a culture of tolerance and coexistence (54,55)? A few years back, an international panel of experts was drawn together to explore perspectives on and experiences with human–wildlife conflicts, and to develop principles for ethical wildlife control (56). The panel determined that a first response to human–wildlife conflict should be to focus on how human behaviour has affected the ecosystem and to address the root causes of conflict rather than only the problematic outcome. There have to be levers into the behavioural modification this requires. If only we took the example of France where it’s Environmental Code, a consolidation of its legislation and decrees on the environment, has as a first General Principle that its wild nature is the heritage of all its people, and that each person has a duty to safeguard and to contribute to the protection of the environment (Article L110-1(I) and Article L110-1-2 in (57)). That takes it away from being in the power of just the land owners and users, and gives everyone in France the responsibility to ensure a right for wild nature to exist without it being screwed over. The General Principles also give a right of access to information and a principle of participation, the detail and circumstances of both of those greatly expanded in later chapters of the Code (Article L110-1(II)(4) & (5) in (57)). I should also note that the Environmental Code incorporates legislation on France’s ecological networks, both terrestrial and aquatic. Its aim is reduce the fragmentation and vulnerability of natural habitats and habitats of species, and identify, preserve and connect the spaces important for the preservation of biodiversity by ecological corridors while taking into account the biology of wild species, so that the genetic exchanges necessary for the survival of species of wild fauna and flora are facilitated (58). Don’t expect to find such ecologically comprehensive language in the Environment Bill. Nature protection is nature conservation Nature protection conserves nature, but we have no concept of strict protection, of the means to restrict human activity that degrades wild nature, and why the lack of reform in the Environment Bill of protected area types is so frustrating (see above). Again, France’s Environmental Code gives example in that a designated nature reserve can be subject to a specific regime that prohibits any actions inside the reserve that are a likely to harm the natural development of fauna and flora: this includes the prohibition of hunting, fishing, agricultural, forestry, pastoral, industrial, commercial, sporting and tourist activities, the performance of public or private works, the use of water, the movement or parking of people, vehicles and animals, mining activities, as well as aeroplane flight over the reserve (Article L332-3 in (59)). The same goes for its National Parks which unlike our own are made up of two zones - a core area surrounded by a partnership or buffer area – and where the core area can be subject to a special regime that prohibits hunting and fishing, commercial activities; and regulates the exercise of agricultural, pastoral or forestry activities, industrial and mining activities; and any action likely to harm the natural development of the fauna and flora and, more generally, to alter the character of the national park (Article L331-4-1 in (60)). In wider scale, the EU has brought out its Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 in which there are key commitments for nature protection by 2030 based on legally protecting a minimum of 30% of the EU's land area and integrate ecological corridors, as part of a true Trans-European Nature Network (61). The real teeth in the commitments is the requirement to strictly protect at least a third of those protected areas, and thus 10% of the EU's land area – it is currently only 3% and we have none. We have nowhere that provides an autonomous space of strict protection for all the species within it. Strict protection does not necessarily mean that the protected area is inaccessible to humans, as a footnote explains, its purpose is to leave natural processes essentially undisturbed in respect for the areas’ ecological requirements. Instinctively, I want wild nature to have its own space where it can act with its own volition, where it has its own existence, but it does need our absolute respect not to interfere or encroach on that space. Resistant as our system of nature conservation is to giving real protection, strict protection to wild nature, our leaving the EU takes away any real pressure there may have been for change. There are so few animals given strict protection under UK legislation, and even then it is by varying degree, such as pine marten, red squirrel, otter, wildcat, dormouse, and beaver in Scotland (62,63). Of those species, the otter and beaver are given both explicit and spatial strict protection as a result of the EU Habitats Directive, which required us for the spatial protection to identify a network of Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) where the habitat needs of those species must be maintained (Article 6, Annex 2 in (64)(65)). I am not aware of any assignment of beaver in Scotland to SACs, given that the acceptance of beaver as a free-living species that then qualified it for strict protection was only very recent (66). It has probably come too late for that process anyway, now we have left the EU. There are, however, 75 SACs for otter where it is either a primary or qualifying feature, most of which are in Scotland and Wales (67,68) and we have had to report periodically to the EU on the conservation status of this species (69). I doubt many people here are aware of this spatial aspect to the strict protection of a species, but that is only half the equation. A comparison of the UK distribution with the location of these SACs shows there are likely to be many otters out of an estimated total population of around 12,000 (69) that are living outside of these protected areas (70). This doesn’t mean to say that these otter aren’t also covered by strict protection everywhere it chooses to exist, as should be clear from the explicit strict protection given to them under the EU Habitats Directive (see Article 12 & Annex IV in (64)). It took a very recent ruling from the Court of Justice of the European Union to clarify this in a very challenging situation, and for an animal that is at the sharp end of human–wildlife conflict. In November 2016, staff from a dog shelter accompanied by a vet captured a wolf that had been hanging around in the Romanian village of Șimon, near Brașov (71-73). The wolf was anaesthetised by the vet, picked up by its tail and the scruff of its neck, and plonked in a cage for transporting dogs. The intention was to relocate the wolf by transporting it to an enclosure intended for wolves coming from non-compliant zoos. However, during this transport, the wolf managed to break out of the cage and fled into the surrounding forest. Subsequently, an animal welfare NGO filed a complaint against this action, claiming it was a breach of many of the aspects of the strict protection of the wolf under the Habitats Directive, and particularly its capturing "in the wild" and transportation. At issue was whether that strict protection still obtained if the wolf was regarded to have been outside its “natural range” when in a human settlement and therefore not "in the wild". The expressions natural range and in the wild are in the wording of Article 12 of the Habitats Directive that confers strict protection (64). In its deliberations, the Court of Justice had to consider whether it would be feasible to make such a distinction, that these did not apply to human settlements, even referring to the provisions for strict protection of the wolf under Article 6 of the Bern Convention (74,75) the Habitats Directive being a transposition of the Bern Convention into EU Law. It was noted that there wasn’t any geographical restrictions laid down in that article of the Bern Convention, and the fact that prohibition extended to “any” form of deliberate capture indicated that it is to be interpreted broadly. The Court therefore decided that the strict protection of animal species provided for in the Habitats Directive also extended to when they leave their natural habitats and stray into human settlements. In addition, they pointed out that capture and relocation of a wolf found in a village can therefore only be justified when a formal derogation from that strict protection to allow capture and translocation is sought and licensed by the competent national authority, and which had not happened in this case. The wolf is no longer an unknown quantity to be feared There is such a rich literature now from Continental Europe to draw from, of recent studies that take away much of the uncertainties about how wolves use landscapes and which lessen fear - I have already described some (55). Here are some more. A study of the movement behaviour over two decades of wolves in Scandinavia found that they consistently avoided human settlements and main roads, and although there were occasional sightings of wolves or their tracks near human settlement, they did not necessarily require management intervention, the authors concluding that communication of scientific findings on carnivore behaviour to the public would in most cases lessen fear in local communities (76). There are a couple of papers on the movement of radio-collared wolves in the Apennines in Italy. The first showed the wolves home ranges were larger during the night and in areas of greater road density, the first finding a reflection of greater movement when the activities of people are less, the second a reaction to the habitat fragmentation created by roads so that the wolves had to increase home range size to encompass retreat areas large enough and secluded enough from human activity (77). There was also a habitat-mediated response to human presence and activity as resident wolves preferentially established core areas at greater elevation and in the more forested and inaccessible portions of the home range. The second found that responses by wolves to anthropogenic features varied according to behavioural state (travelling vs. resting) and social affiliation (pack members vs. floaters) (78). During summer, pack members strongly avoided roads and settlements throughout the day, both when travelling and resting, selecting forested areas and shrublands. During autumn and winter, when human activity was less, pack members travelled closer to main roads and settlements, but they still selected resting sites farther from anthropogenic features and located them in denser cover and along steeper slopes. Compared to pack members, floaters, when travelling, showed a weaker avoidance of main roads and settlements and did not show any selection pattern towards environmental variables. When resting, contrary to pack members, floaters selected sites closer to main roads and settlements, even though these were still located along denser cover and steeper slopes. There is also much now known about the public’s reaction to the return of wolves. Thus the Dutch Minister of Agriculture Nature and Food Quality has recently published a report on the public support for the resettlement of wolves in the Netherlands (79). Wolves have been roaming into the Netherlands from Germany since 2015, a study in 2018 showing that there were eight different wolves present, and then in 2019 a pair of wolves that had settled in the forest of northern Veluwe produced the first offspring. In many ways, the results of the Dutch survey mirror those of a similar survey carried out in Germany (55). It shows that 57% of the Dutch have a positive attitude towards the resettlement of the wolf and 65% see the wolf as harmless. Most people would find encountering a wolf in the wild an exciting (66%) and special (77%) experience, the latter rising to 81% amongst residents of areas where wolves are present. Just under half (45%) would like to experience a wolf encounter in the wild, and that was 64% amongst those who were advocates for the return of the wolf. The Dutch also expressed their intention to continue visiting nature areas where wolves occur (60%) that proportion being higher amongst inhabitants of wolf areas (64%) and advocates for wolf return (83%). The survey showed that Dutch were aware that the wolf is a protected species in Europe (58%) that they are shy animals and in principle do not attack humans (75%). They are curious about where wolves stay in the Netherlands and in which areas they will roam (66%). The Dutch know that wolves occasionally eat sheep (64%) but that deer, wild boar and small rodents make up most of their diet (61%). Where 72% of proponents think that there is enough nature and space for wolves, 75% of opponents think that this is not the case. Most Dutch people believe that farmers should be compensated (partly) by government for the damage caused by wolves (73%). They also believe that the government should support farmers by (partially) reimbursing for preventive measures against the wolf (68%). Tellingly, Dutch people who are against the return of the wolf more often wrongly think that wolves that live close to livestock eat sheep and goats more often (68%). It is important to understand the implications of strict protection The strict protection afforded to a range of species under the Bern Convention and the Habitats Directive were measures in pursuit of protecting and thus conserving species on the edge that had dwindled through human persecution. It was also important that if these species reappeared in countries either through voluntary or deliberate reinstatement – both the Bern Convention and the Habitats Directive require consideration of reinstatement for former native species no longer present (see Article 11 in (74) and Article 22 in (64) - then it was necessary to give that strict protection while they were re-establishing themselves towards effective populations in their former native range. The strict protection afforded to the wolf is why its voluntary expansion westward through Continental Europe has been so successful. The strict protection for the wolf has also had the effect of a compulsion on land users to learn to deal with human-wildlife conflicts in constructive ways. Thus there are many examples across Continental Europe of information, support and funding being available either from Governments, rural or voluntary organisations to help prevent predation of livestock and reduce conflict, as well as compensation when predation of livestock by wolves can be shown (80-82). The Netherlands has an inter-provincial wolf plan agreed in 2019, as the 12 provinces are legally responsible for nature policy in relation to the wolf (83). It is a comprehensive document, covering aspects of species protection; points out that farmers are themselves legally responsible for taking preventive measures to protect livestock from predation by the wolf; describes the evidence required to qualify for compensation for a wolf kill; points to the subsidies that some of the provinces provide to pay for preventive measures; and it covers monitoring and reporting of the wolves presence and impact. The provincial administration service BIJ12 in the Netherlands is responsible for implementing rural matters on behalf of the 12 provincial governments. It is thus responsible for communication and information regarding wolves and damage to farm animals, as well as monitoring the development of wolves in the Netherlands, and processes reports of suspected wolf sightings, wolf tracks, and farm animals and/or wild animals killed by wolves. Its main wolf page has links to current monitoring data on wolves, information on valuing compensation for wolf damage; a running list of reported attacks on farm animals; as well as links to policy and information documents (84). It also links to the module for wolves in its Fauna Damage Prevention Kits (85). This describes in some detail preventive measures, such as various fencing designs; herd guard dogs; stock penning at night; and red flutter ribbons dangling from wires stretched between posts (fladry lines) that act as a visual scare and distractant. Why the wolf must be reinstated I recently remarked that the greatest natural experiment in reinstatement of trophic ecology has taken place through the voluntary westward expansion of wolves in continental Europe so that there is now a presence in every country (55) – video footage of the first wolf pups born in Belgium for 150 years has just been released (86). That natural experiment could be taking place here if we reinstated the wolf. It would drive a process of determining the ecological flow that would exist for the wolf – a hugely revealing process, as well as a great opportunity to engage people in ecological understanding. It would break through the power and ownership structures, its impact forcing land users to face up to human-wildlife conflicts in constructive ways, as its strict protection under the Bern Convention would apply here (87). It would be a catalyst for reframing our outlook and policies on wild nature, and thus has the potential to change the paradigm from nature conservation to nature protection – protecting nature from us. As an expression of public will, it would give us a stakeholding in our wild heritage from which we have long been excluded.

Nothing will change though if we allow the power

and ownership structures to continue to dictate and block, and the adherents

to conservation rather than protection to hold sway. We must stop letting them

speak for us, challenge their presumption to dictate to us. Like Michael Soulé,

I know we have the science and resources to secure a future for our wild

nature that gives hope, and widespread participation in determining the

ecological flow of wolves is a constructive and significant way for making use

of that science and resources. While Michael was primarily an enabler of hope,

he could also throw out a thought provoking caution when he saw human nature

get in the way of that hope. His last words to me were in response to warnings

I sent around various scientists in April that the ecological basis of

rewilding was malignly being undermined by forces that sought to downplay

predation in trophic ecology (88) indicating that there needed to be a

reassertion of the scientific basis of rewilding. This was his reply, a

critique so simple but so powerful as a call to action: Mark Fisher 5 July 2020 (1) Mabey, R. (1986) Gilbert White: A Biography of the Author of The Natural History of Selborne, Century Hutchinson https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ME43SXf4rDkC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false (2) White, G. (1789) The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne in THE COUNTY OF SOUTHAMPTON 1789 https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=cVkEAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false (3) East Hampshire Hangers Special Area of Conservation, JNCC https://sac.jncc.gov.uk/site/UK0012723 (4) Wilderness uncovered - the past and future of drowned lands, Self-willed land November 2016 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/doggerland.htm (5) Montgomery, W. I., Provan, J., McCabe, A. M., & Yalden, D. W. (2014). Origin of British and Irish mammals: disparate post-glacial colonisation and species introductions. Quaternary Science Reviews, 98, 144-165 (6) Large carnivores as the focal species for reinstatement of natural processes in Britain, Self-willed land November 2014 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/focal_species.htm (7) Lovegrove, R. (2007) Silent Fields: The Long Decline of a Nation's Wildlife. OUP https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=HNLiStFz6GUC&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false (8) The Disappearance of Wolves in the British Isles, Ivy Stanmore, Wolf Song of Alaska https://www.wolfsongalaska.org/chorus/?q=node/230 (9) Ecological consequence of predator removal, Self-willed land July 2014 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/predator_removal.htm (10) Wild Law - giving justice to the earth, Self-willed land October 2007 http://www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/wild_law.htm (11) UK Restoration and Rewilding Plan - a positive action-oriented narrative, Self-willed land November 2019 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/plan.htm (12) Environment Bill 2019-21, Parliament Bills and Legislation https://services.parliament.uk/bills/2019-21/environment.html (13) Environment Bill 009 2019-21 (as introduced) https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-01/0009/20009.pdf (14) GOVERNMENT COULD PUSH AHEAD WITH FREE GARDEN WASTE COLLECTIONS, SAYS EUSTICE, Resource 18 June 2020 https://resource.co/article/government-could-push-ahead-free-garden-waste-collections-says-eustice (15) Rutz, C., Loretto, M., Bates, A.E. et al. COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife. Nature Ecology & Evolution (2020) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-020-1237-z (16) A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment, HM Government 2018 (17) Written evidence submitted by the 49 Club (EB01) Environment Bill Session 2019-21 https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmpublic/Environment/memo/EB01.htm (18) The continuing destruction of our native trophic pyramid, Self-willed land February 2018 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/spiral_down.htm (19) Notices of Amendments: 2 June 2020 Environment Bill, continued. Parliament Bills and Legislation (20) Boitani, L., Falcucci, A., Maiorano, L., & Rondinini, C. (2007). Ecological networks as conceptual frameworks or operational tools in conservation. Conservation biology, 21(6), 1414-1422 https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00828.x (21) Bennett, G., and P. Witt. 2001. The development and application of ecological networks: a review of proposals, plans and programmes. Report B1142. World Conservation Union (IUCN), Gland, Switzerland. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2001-042.pdf (22) National Natural Capital Atlas: Mapping Indicators (NECR285) Natural England February 2020 http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/file/4728259965353984 (23) Section 41, Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/16/section/41 (24) Crosher & Humphrey Crick, Natural England November 2018 https://cieem.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/6.-Ian-Crosher.pdf (25) National Habitat Network Maps, User Guidance v.2, Natural England May 2020 https://magic.defra.gov.uk/Metadata_for_magic/Habitat%20Network%20Mapping%20Guidance.pdf (26) Habitat Networks (Combined Habitats) (England) (27) Habitat Networks (England) Natural England May 2020 https://data.gov.uk/dataset/0ef2ed26-2f04-4e0f-9493-ffbdbfaeb159/habitat-networks-england (28) The moral corruptness of Higher Level Stewardship, Self-willed land August 2013 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/corrupt_hls.htm (29) Flooding and cherry picking, Self-willed land February 2014 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/flooding_cherry_picking.htm (30) Mainstone, C.P., Jefferson, R., Diack, I, Alonso, I, Crowle, A., Rees, S., Goldberg, E., Webb, J., Drewitt, A., Taylor, I., Cox, J., Edgar, P., Walsh, K. 2018. Generating more integrated biodiversity objectives – rationale, principles and practice. Natural England Research Reports, Number 071. http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/file/5745532112994304 (31) Perry, S., Goldberg, E., Wilkins, T., Howe, C., Cox, J., Drewitt, A (2018) Appendix A – Woodland habitats. Generating more integrated biodiversity objectives – rationale, principles and practice. Natural England Research Reports, Number 071 http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/file/5697817777799168 (32) Langford, P., Larwood, J., Lusardi, J., Appleton, D., Brotherton, P. N. M., Duffield, S. J. & Macgregor N. A. (2020) Nature Networks Evidence Handbook - Creating Nature Networks for Wildlife & People. Natural England Research Report NERR081. Natural England http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/file/4549738454319104 (33) Michael Soulé, father of conservation biology, dies at 84, Jennifer McNulty, UC Santa Cruz Newscenter June 23, 2020 https://news.ucsc.edu/2020/06/soule-obituary.html (34) In Memory of Michael Soulé, Project Coyote http://www.projectcoyote.org/about/michael-soule/ (35) Soulé, M. E. (1999) An Unflinching Vision: Networks of People for Networks of Wildlands. Wild Earth 9(4)(Winter 1999/2000) 38-46 http://www.environmentandsociety.org/sites/default/files/key_docs/rcc_00097009_4_1.pdf (36) Conserving large mammals and their habitat as incentive for ecological sustainable development of a Romanian municipality, Rewilding Foundation (37) Fisher, M. (2020) NATURAL SCIENCE AND SPATIAL APPROACH OF REWILDING: Evolution in meaning of rewilding in Wild Earth and The Wildlands Project, Self-willed land March 2020 http://www.self-willed-land.org.uk/rep_res/REWILDING_WILDEARTH_WILDLANDS_PROJECT.pdf (38) Miller, B., Foreman, D., Fink, M., Shinneman, D., Smith, J., DeMarco, M., Soulé, M. and Howard, R. (2003). Southern Rockies wildlands network vision: A science-based approach to rewilding the southern Rockies. Southern Rockies Ecosystem Project and Wildlands Project https://wildlandsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/S.-Rockies-WND.pdf (39) Maanen, E. van, G. Predoiu, R. Klaver, M. Soulé, M. Popa, O. Ionescu, R. Jurj, S. Negus, G. Ionescu, W. Altenburg 2006. Safeguarding the Romanian Carpathian Ecological Network. A vision for large carnivores and biodiversity in Eastern Europe. A&W ecological consultants, Veenwouden, The Netherlands. Icas Wildlife Unit, Brasov, Romania. http://www.rewildingfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/carnivores_carpathian_vision.pdf (40) Carver, S. & Fisher, M. (2012) MAPPING WILDERNESS IN EUROPE AND BEYOND, WRi, ECCB Glasgow September 2012 http://www.self-willed-land.org.uk/rep_res/ECCB_STEVE_MF.pdf (41) Anderson, M.G., Barnett, A., Clark, M., Prince, J., Olivero Sheldon, A. and Vickery B. 2016. Resilient and Connected Landscapes for Terrestrial Conservation. The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science, Eastern Regional Office. Boston, MA. (42) Conservation biology and the repair of our damaged and degraded ecosystems, Self-willed land April 2018 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/strongly_interactive.htm

(43) Carrao, H., Kleeschulte,

S., Naumann, S., Davis, M., Schröder, C., Malak, D.A., and Conde, S. (2020)

Contributions to building a coherent Trans-European Nature Network. European

Environment Agency and European Topic Centre on Urban, Land and Soil Systems (44) Marrec, R., Moniem, H. E. A., Iravani, M., Hricko, B., Kariyeva, J., & Wagner, H. H. (2020). Conceptual framework and uncertainty analysis for large-scale, species-agnostic modelling of landscape connectivity across Alberta, Canada. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1-14 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-63545-z (45) McRae, B. H., Dickson, B. G., Keitt, T. H., & Shah, V. B. (2008). Using circuit theory to model connectivity in ecology, evolution, and conservation. Ecology, 89(10), 2712-2724. http://www.ripuc.ri.gov/efsb/efsb/SB2015_06_Invenergy_comings_J.pdf (46) Dickson, B.G., Albano, C.M., McRae, B.H., Anderson, J.J., Theobald, D.M., Zachmann, L.J., Sisk, T.D. and Dombeck, M.P. (2017) Informing strategic efforts to expand and connect protected areas using a model of ecological flow, with application to the western United States. Conservation Letters, 10(5), pp.564-571. https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/conl.12322 (47) Baumann, M., Kamp, J., Pötzschner, F., Bleyhl, B., Dara, A., Hankerson, B., Prishchepov, A.V., Schierhorn, F., Müller, D., Hölzel, N. and Krämer, R., Declining human pressure and opportunities for rewilding in the steppes of Eurasia. Diversity and Distributions 00:1–13 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/ddi.13110 (48) They shoot foxes, don't they? Self-willed land January 2007 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/shoot_foxes.htm (49) Nature grooming - the killing of wildness in nature, Self-willed land April 2007 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/nature_grooming.htm (50) Giving natural justice to wild nature, Self-willed land January 2017 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/badger_slaughter.htm (51) Protection of Badgers Act 1992, C. 51 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1992/51 (52) Guest blog – Licensed Badger Killing; Ethical Considerations, Alick Simmons, MARK AVERY: STANDING UP FOR NATURE 16 December 2019 (53) SNH Beaver licensing summary 1st May to 31st December 2019, Scottish Natural Heritage (54) An ecological landscape – connectivity, cores and coexistence, Self-willed land March 2019 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/connectivity.htm (55) The separation between wolves and humans in modified landscapes, Self-willed land April 2020 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/wolves_humans.htm (56) Dubois, S., Fenwick, N., Ryan, E.A., Baker, L., Baker, S.E., Beausoleil, N.J., Carter, S., Cartwright, B., Costa, F., Draper, C. and Griffin, J. (2017) International consensus principles for ethical wildlife control. Conservation Biology, 31(4): 753-760 https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/cobi.12896 (57) Principes généraux, Code de l'environnement (58) Article L371-1. Titre VII: Trame verte et trame bleue. Code de l'environnement (59) Section 1 : Réserves naturelles classées, Sous-section 1 : Création, Code de l'environnement (60) Section 1 : Création et dispositions générales, Chapitre Ier : Parcs nationaux, Code de l'environnement (61) EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 -Bringing nature back into our lives, COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS, EUROPEAN COMMISSION, COM(2020) 380 final, Brussels, 20.5.2020 https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/communication-annex-eu-biodiversity-strategy-2030_en.pdf (62) SCHEDULE 5, Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1981/69/schedule/5 (63) SCHEDULE 6ZA, Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1981/69/schedule/6ZA (64) COUNCIL DIRECTIVE 92 /43 /EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31992L0043&from=EN (65) Guidance document on the strict protection of animal species of Community interest under the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC, February 2007 https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/guidance/pdf/guidance_en.pdf (66) Beavers given protected status, Scottish Governement News 23 Feb 2019 https://www.gov.scot/news/beavers-given-protected-status/ (67) Species list, SAC, JNCC https://sac.jncc.gov.uk/species/ (68) 1355 Otter Lutra lutra, SAC, JNCC https://sac.jncc.gov.uk/species/S1355/ (69) Conservation status assessment for the species: S1355 Otter (Lutra lutra) Fourth Report by the United Kingdom under Article 17 on the implementation of the Directive from January 2013 to December 2018, European Community Directive on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora (92/43/EEC) https://jncc.gov.uk/jncc-assets/Art17/S1355-UK-Habitats-Directive-Art17-2019.pdf (70) Comparison of UK resource and SAC distribution of Annex II species 1355 Otter Lutra lutra, JNCC https://sac.jncc.gov.uk/species/S1355/comparison (71) OPINION OF ADVOCATE GENERAL KOKOTT delivered on 13 February 2020 (1) Case C‑88/19 (72) The strict protection of animal species provided for in the Habitats Directive also extends to specimens that leave their natural habitat and stray into human settlements. Judgment in Case C-88/19 Alianța pentru combaterea abuzurilor v TM and Others Court of Justice of the European Union PRESS RELEASE No 72/20 Luxembourg, 11 June 2020 https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-06/cp200072en.pdf (73) Renvoi préjudiciel – Conservation des habitats naturels ainsi que de la faune et de la flore sauvages – Directive 92/43/CEE – Article 12, paragraphe 1 – Système de protection stricte des espèces animales – Annexe IV – Canis lupus (loup) – Article 16, paragraphe 1 – Aire de répartition naturelle – Capture et transport d’un spécimen d’animal sauvage de l’espèce canis lupus – Sécurité publique. ARRÊT DE LA COUR (deuxième chambre) 11 juin 2020 (74) Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, Details of Treaty No.104, Council of Europe, Bern, 19.IX.1979 https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=0900001680078aff (75) Appendix II – STRICTLY PROTECTED FAUNA SPECIES, Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, Details of Treaty No.104, Council of Europe, Bern, 19.IX.1979 (76) Carricondo-Sanchez, D., Zimmermann, B., Wabakken, P., Eriksen, A., Milleret, C., Ordiz, A., Sanz-Perez, A. and Wikenros, C., 2020. Wolves at the door? Factors influencing the individual behavior of wolves in relation to anthropogenic features. Biological Conservation, 244: 108514. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320719318725 (77) Mancinelli, S., Boitani, L., & Ciucci, P. (2018). Determinants of home range size and space use patterns in a protected wolf (Canis lupus) population in the central Apennines, Italy. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 96(8): 828-838 https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/89374/1/cjz-2017-0210.pdf (78) Mancinelli, S., Falco, M., Boitani, L., & Ciucci, P. (2019). Social, behavioural and temporal components of wolf (Canis lupus) responses to anthropogenic landscape features in the central Apennines, Italy. Journal of Zoology, 309(2), 114-124 https://zslpublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jzo.12708 (79) Maatschappelijk draagvlak voor de hervestiging van de wolf in Nederland, Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit Maart 2020 (80) Cry wolf - the return of Britain's top predator, February 2015 www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/cry_wolf.htm (81) The greatest challenge for living with wolves rests within the human mind, November 2017 http://www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/wolf_conflict.htm (82) Linnell, J. D. C. & Cretois, B. 2018, Research for AGRI Committee – The revival of wolves and other large predators and its impact on farmers and their livelihood in rural regions of Europe, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/617488/IPOL_STU(2018)617488_EN.pdf (83) IPO (2019) Interprovinciaal wolvenplan. IPO, Den Haag. https://www.bij12.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Interprovinciaal-wolvenplan.pdf (84) Wolf, Bij12 https://www.bij12.nl/onderwerpen/faunazaken/wolf/ (85) Module Wolven, Faunaschade PreventieKit, Bij12 https://www.bij12.nl/onderwerpen/faunazaken/faunaschade-preventiekit-fpk/module-wolven/ (86) Flanders’ wolf pups captured on camera for first time, Lisa Bradshaw, Flanders Today 24 June 2020 http://www.flanderstoday.eu/flanders-wolf-pups-captured-camera-first-time

(87) Implications for wild

land on leaving the European Union, Self-willed land July 2016

(88) Faking the wild – safari

park rewilding, Self-willed land May 2020 url:www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/ecological_flow.htm www.self-willed-land.org.uk mark.fisher@self-willed-land.org.uk |