The scientific wilderness

Surtsey Reserve

Undisturbed nature as a long-term, open-air laboratory is a reference space that symbolizes wilderness. The scientific wilderness is thus more than just an academic pursuit, it is where we learn the absolute importance of the self-will of existence of wild nature. Observation of that self-will of existence is a compelling argument for its recovery and reconnection

The decision of the Swiss government last year to change hunting rules to allow preventative killing of wolves opened a floodgate of applications from cantons, the member states of Switzerland, to eradicate whole packs of wolves (1,2). The canton of Graubünden in southeastern Switzerland took up the opportunity, the Federal office for the Environment (FOEN) granting the state permission to proactively regulate its wolf population so that out of a current population of around 130 (3) a maximum of 44 wolves could be shot in the canton by the end of the permitted period in January 2024 (4). The canton had planned to completely remove four wolf packs and reduce the number in two others, but a complaint by several nature conservation organizations to the Federal Administrative Court (5) caused a hold nationally on the wolf culls, and stopped removal of two of the packs and the reduction in numbers of two others, but 20 wolves were still killed (6).

The next legally stipulated regulation period for removing wolves began on 1 September 2024 and will last until 31 January 2025. The canton of Graubünden submitted an application in August to kill two thirds of the confirmed young animals in all packs that had current offspring (7). In addition, the removals of two wolf packs were requested. The canton explained that the aim of those regulatory measures was to reduce conflicts in the agricultural sector and to increase shyness in wolves towards humans without endangering the wolf population. Having had approval of that application from FOEN in early September, the canton ordered that 22 wolf cubs in the seven wolf packs with confirmed offspring were to be killed, as well as the removal of an entire wolf pack (8). A second application was also made at that time for the removal of two wolf packs due to conflicts with agriculture, one of those being the Fuorn wolf pack, named after the Italian for Ofen. Ofen Pass is a high alpine mountain pass in the canton of Graubünden, the significance of this will become clear later.

Sound scientific knowledge about the ecosystems of the Swiss National Park

Permission for the removal of the Fuorn wolf pack brought forth a press release (9) and comprehensive position statement from the Research Commission of the Swiss National Park (10) the Commission being drawn up from members of the Swiss Academy of Science with research projects inside the Park (11). The statement noted that the Commission’s task was, among other things, to coordinate the acquisition of sound scientific knowledge about the ecosystems of the Swiss National Park, which is located within the canton of Graubünden (12,13) and to make this available to support the park's protection mandate. From a scientific point of view, the Commission judged that shooting all of the Fuorn wolf pack, which lives mainly in the Swiss National Park, was not justifiable, since the attacks on cattle in August that had led to the application by the canton of Graubünden had been carried out by a lone female wolf that had not been part of the Fuorn pack for many months, and had now disappeared ((10) and see (14)). It was noted that the shooting of large predators often did not reduce the number of future livestock attacks and sometimes an increase in attacks was observed. While the removal of that lone female could have been considered, it had to be taken into account that the Fuorn pack was an important part of the natural dynamic of the protected ecosystem of the Swiss National Park.

The statement went on to say that the wolves anyway, could not be killed inside the National Park due to its legislative status, and thus removal could only take place when the wolf pack left the perimeter of the National Park. Even then, removal outside the Swiss National Park would directly influence the wolf population inside the National Park and thus have a significant impact on the legally anchored, natural development of nature in the Swiss National Park. A decision to remove the Fuorn wolf pack would therefore counteract the legal mandate to protect nature in the Swiss National Park. Unfortunately, within days of the position statement, FOEN approved the application from the canton of Graubünden to remove the Fuorn wolf pack (15). This brought forth a statement from the Swiss National Park that pointed out that the decision had been made before the wolves responsible for a second cattle attack in the Val Mora could be identified, and regretted that a less drastic solution could not have been found that did justice to the Swiss National Park and its national protection mandate (16).

It is important here to recognise the legal status of the Swiss National Park, as reflected in the first article of its Federal legislation, entitled Nature and Purpose, which says the Swiss National Park is “… a reserve where nature is protected against any human intrusions and in particular where all flora and fauna is allowed to develop naturally”(17). As the Research Commission’s position statement said, the protection of the of wolves was therefore also enshrined in law in the Swiss National Park. There is an equally important clause in that article - “The Park shall be the subject of continuous scientific research”. Hence the existence of the Research Commission of the Swiss National Park. It was this twin aspect of the Swiss National Park, and the early history of its formation in 1914, that made it a valuable example when I wrote a book chapter about the ecological values of wilderness in Europe (18).

The creation of larger nature parks in which everything that was originally native gets permanent asylum

Undisturbed nature as a long-term, open-air laboratory, was at the heart of a speech to the Swiss National Council, given in early 1914 by Council Member Dr Walter Bissegger in support of a resolution to establish the Swiss National Park (19). This was the culmination of a decade of development of a vision of setting aside an area of land where nature could develop without human disturbance. Bissegger’s speech opened by pointing to the power that humans had to modify landscapes to their own benefit. It had, however, come with a cost in Switzerland, Bissegger noting with regret the extinction of lynx, wildcat, bear, ibex (Capra ibex) and vulture (Gypaetus barbatus)these species once being the pride of the country. He also bemoaned the losses of songbirds, and the mass tearing out of wildflowers, such as Edelweiss (Leontopodium alpinum). Bissegger was persuaded that there was only one means to effectively counter the gradual destruction, which was through “the creation of larger nature parks in which everything that was originally native gets permanent asylum”

Bissegger described that the proposed location for a National Park, an area of 170km2 in the eastern Alps, was composed of rugged, bare mountain peaks and ridges, alpine meadows, and deep river valleys forested with pine and other conifers, all with an abundant and characteristic flora. The choice of Ofen Pass was for a very practical reason: the valleys were for the most part completely uninhabited so that their use in forestry and farming was unimportant because of inaccessibility. He noted that the area had been commended for its botanical value by Prof. Carl Schröter, a Swiss phytogeographer, thus providing a good opportunity for scientific study. Bissegger also pointed to the hope expressed by Professor Freidrich Schokke, a Swiss Zoologist, that the mammals lost to the area would migrate back in under the conditions of a strict reserve. The question Bissegger put to his fellow Council members was whether they wanted to “create such a sanctuary for animals and plants, as far as possible excluded from any human impact, an area in which for 100 years there would be no economic use from forestry, grazing and hunting, and where no axe, nor the sound of shooting would be heard?”

The Council agreed, and the Federal Decree on the establishment of a Swiss National Park was enacted on the 3 April 1914 and came into force in August 1914 (20). The Research Commission was created in 1916 (21) the first long-term observation areas in the Park were set up in 1917 (22) and in 1920, a strategy for the long-term research in the park was laid out by Prof Carl Schröter (23). He noted that the Park would be invaluable for scientific study because of the absolute elimination of interference by humans. He observed that all the previous changes to the original state through the long-lasting effects of centuries of human modification would disappear with time and the old original life community would be produced again - "A great "wilderness experiment" will be carried out there. To follow all stages of this wilderness, this return to the original state, this “retrograde succession” in the greatest detail, is a main task of scientific observation, which must of course extend over a very long period of time"

That first article of the Federal Decree from 1914 is carried through to this day in the current legislation, with its stipulation for undisturbed nature and scientific observation. In addition, the Park has its own, detailed Protection Regulations that prohibit littering, removing any natural or geological object, visiting outside of daylight, cycling, use of drones, stepping off marked paths, bathing in any natural water feature, and entry during winter (23). Further, an Ordinance for protection of the National Park by the canton of Graubünden lists many of those prohibitions, but also specifically bans hunting, fishing, cattle grazing, and entry to persons under 15 years old unless accompanied by an adult (24). It is for these reasons, and because of the aspirations and expectations of scientists like Prof Carl Schröter (see above) that the Swiss National Park often refers to itself as a developing wilderness, the largest in Switzerland – “Allowing wilderness has been the declared goal of the Swiss National Park since its founding. As an internationally recognized wilderness area, it meets the strictest standards that exist for protected areas” (25). The Park also points to its protection status being designated under IUCN Category Ia, a strict nature reserve (26) As the IUCN Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories suggest, IUCN Category Ia strict nature reserves can serve as indispensable reference areas for scientific research and monitoring (27).

A 20-year program of wolf monitoring

Wolves had not yet returned to the area of the Swiss National Park when I wrote that book chapter, but I noted that while the Park had no plans to reintroduce them, it looked forward to the return of large predators, as the impact of herbivores like red deer was taking its toll on forest regeneration as well as disrupting the food supply of other species (18). I reported that a research project into the trophic relationship structure and its dependencies was started in 2009 by erecting fencing to specifically exclude various herbivorous animal groups (ungulates, marmots and hares, mice) and examine how the ecosystem responded to these exclusions. I find out now that a female wolf had first been seen roaming the Park area in December 2016 and continued to do so (28). From the end of October 2022, Park employees and the cantonal game warden were able to repeatedly find traces of two wolves, a male and a female, inside and outside the Park, and capturing them with camera traps. Evidence that they had formed a pack came in September last year when images from camera traps in the Ofen Pass area showed at least four young animals (now confirmed as eight (29)) the first evidence of a litter of wolf cubs in over a hundred years in southeastern Switzerland. Deer and chamois were also found killed by wolves in the same area. In early summer this year, numerous carcasses of ungulates were found in the Park, and subsequent camera trap evidence showed that the Fourn wolf pack had produced another three cubs (29). It later turned out that there were are at least seven young wolves (14).

As befits the purpose of the Swiss National Park, as soon as that first wolf was sighted in 2016, the Park instigated a 20-year program of wolf monitoring to determine the influence of wolves on the trophic food web of the Park (30). The reasoning for starting it then was that the increasing spread of wolves in the Alpine region meant that a wolf pack was expected to form in the Swiss National Park area in the coming years. Evidence collected until that occurred would be acoustic recordings in late summer and autumn, as well as camera trap images, footprints, faeces samples, and direct observations and kills of wild ungulates. The composition of the diet would be determined from the faeces samples using microscopic methods, and the genetic identity of wolves would be compared with known wolves in Switzerland.

I want to go back to the statement that the Park released on hearing that the application to remove the Fuorn wolf pack had been granted, because it underscores the dire nature of the decision (see above). The Park was convinced that a consensus about the impact of wolves could only be reached if there was a social willingness to grant the wolf a fundamental right to exist as an internationally protected species, pointing out that wolves do not adhere to boundaries defined by humans (16). It explained that over the 110 years since the Park’s foundation, effective and scientifically sound management solutions had been found in and around the Park for other species such as ibex and red deer. It noted that technical knowledge was the basis of all these decisions. It pointed out that there was still much to be addressed within the Park, including insights into the population development of the wolf, but also into the effects of the wolf's presence on other animal species, and on the vegetation through reducing damage caused by browsing in the forests around the Park – “Ongoing research projects in the Swiss National Park will be severely affected by the decision to shoot the animals”. Poised at last to observe the long-term impact of wolves on the trophic ecology of the Swiss National Park, the opportunity was going be snuffed out.

I cannot bring myself to check whether the slaughter of these wolves has commenced. This is especially so since it appears that a complaint last year by CHWolf, a Swiss wolf protection association (31) to the Council of Europe that Switzerland’s new wolf culling policy violated the strict protection afforded to wolves under the Bern Convention, and to which Switzerland must adhere, appears to have paid off. After receipt of responses this year from the Swiss Government (32) the complaint was discussed at a meeting in mid-September of the Bureau of the Bern Convention, the meeting report only recently published (33). The Bureau reiterated that only serious damage could give grounds for the use of an exception on strict protection in Article 8 of the Bern Convention, and expressed concern that “potential damage” constituted a misinterpretation of that Article. The article should only be used in the event of serious damage when all other measures have had no effect. The Bureau remained concerned with the potential extent of wolf culling as a result of the threshold of an “arbitrary minimum number of packs as low as 12”. It regarded this as a “politically motivated, proactive, so preventative, and reactive regulation, leading to a large-scale culling”. The Bureau expressed concern about “reported inaccurate controls of damages caused by wolves and alleged manipulation of data for the purpose of justifying further culling”. It thus blew away the central tenet of the new culling policy (see above). The Bureau also stressed that ensuring compliance with the Bern Convention remained at the federal level, irrespective of the internal organization within a signatory state, such as Switzerland handing it off to its system of cantons. Arbitrary minimum, politically motivated, inaccurate controls, manipulation of data – strong condemnatory words. While this was not an official censure of the culling policy, a decision to do so could be made at the next Standing Committee Meeting of Bern Convention, which is scheduled to take place in early December (34).

Integral reserves established in order to ensure, for scientific purposes, greater protection of fauna and flora

I wrote a few years ago about a new National Park in France to the SE of Paris (35). The Parc national de forêts opened in 2019 and covers an area of 2,410km2. Like all French National Parks since 2006, there is a regulated core area – 560km2 in Parc national de forêts – which is surrounded by a membership or partnership area (36). The core area of the Parc national de forêts Is heavily forested (95%) giving the Park its name, and which is subject to restrictions on activities compared to the partnership area. These were shown in the Park’s Charter and the legislation setting the Park up, and which I described as being regulation of the forestry in the core area, with no deforestation to open space allowed, and restrictions on logging that had visual impact, or may be detrimental to the conservation of wild species and habitats, and which may harm hydrology or archaeological remains. As I also noted, there was to be a strict reserve - réserve intégrale – of 31km2 inside the core area that was to be a site of long-term scientific study of the restoration of an exploited forest to a natural state and functioning, since much of the woodland in the core area had been working forest.

This strict, integral reserve was not mentioned in the Park’s legislation, but was codified in a decree in 2021 (37). The decree stated that its name would be the Arc-Châteauvillain integral forest reserve, and that the Park authorities would ensure enhanced protection of its flora and fauna for scientific purposes. The scientific council of the Park would have a say on that protection, as well on what scientific studies could be undertaken. In terms of that protection, the following were prohibited: any taking of animals, plants, fungi or minerals; quarrying; hunting, agricultural and pastoral activities; commercial or craft activities; camping and bivouacking; public events; access, movement and parking of motorized or non-motorized vehicles, or domestic animals; and forestry activities. Not surprisingly, given these protections, the Arc-Châteauvillain integral forest reserve was classified under IUCN Category Ia (38).

I first came across integral reserves in the core areas of France’s National Parks when I wrote a report in 2010 for the Scottish Government on the status and conservation of wild land in Europe (39). At that time, there were only two designated, one in Ecrins National Park in Alps south of Grenoble (40) and the other in Port-Cros National Park on the coast east of Toulon (41). I knew little about them, not even that they were confined to the core areas of National Parks in France, which is not the case for most of the protected areas in Europe classified under IUCN Category Ia. I have since found a first mention of them in legislation in France for National Parks from 1960 (now repealed) where it says special constraints on areas called integral reserves may be issued by decree in order to ensure, for scientific purposes, in one or more specific parts of a national park, greater protection of certain elements of the fauna and flora (see Article 2 in (42)). Today, it says in Frances Code of Environment that “areas called "integral reserves" can be established in the core of a national park in order to ensure, for scientific purposes, greater protection of certain elements of the fauna and flora. Special requirements may be laid down by the decree which establishes them” (43)

A space that symbolizes the wilderness

I have also found out more about the integral reserve in Ecrins National Park, which the Park describes as a “scientific instrument” a “laboratory space” a “reference space” a “space that symbolizes the "wilderness"”, the aim of which is to “to monitor the natural dynamics of ecosystems little subject to human action” (44, 45). Ecrins National Park came into being in 1973, and the Lauvitel integral reserve within its core area of 920km2 was designated in 1995, the first such designation in France (46). The Park says that the high end of the Lauvitel Valley in the commune of Bourg d'Oisans was chosen because it was naturally protected due to the difficulties in access to this deep V-shaped valley (44). The 6.89 km2 of the integral reserve, with its forested lower slopes, alder scrub, mixed heathland, alpine grassland, moraines and bare rock, rising 1,700m in elevation (45) are deemed to have the highest level of protection in France – its access is strictly prohibited to the public (45,47). The decree establishing Lauvitel says that the reinforced protection of the fauna and flora is for scientific purposes, and that the scientific council of the Park would have a say on that protection, as well on what scientific studies could be undertaken (48). As well as the restriction on access, except those temporarily authorised by the scientific committee, there were prohibitions on any exploitative, extractive activity. As would be expected, Lauvitel integral reserve was classified in 2012 under IUCN Category Ia (44, 49).

A key part of the research in Lauvitel since 1995 has been constant monitoring of its species (50). Thus, amongst the inventories, a total of 63 birds, and 29 mammals have been observed, including grey wolf, red fox, red and roe deer, ibex, wild boar, pine marten, heron (Ardea cinerea) Tengmalm's Owl (Aegolius funereus) black woodpecker (Dryocopus martius) golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) and various species of bats (51) 523 vascular plants, including its trees, shrubs, grasses and wildflowers (52) 208 species of lichens and lichen-associated fungi (53) and 285 fungi of which 166 were saproxylic (dependent on dead or decaying wood)(54). While the monitoring of species continues, a priority action identified was the study of the relationships between these inventoried species and the evolution of the ecosystems in the reserve (45). Current long-term environmental studies include monitoring the evolution of the mountain ecosystems, alpine grasslands, and forests, so that they may be a reference of undisturbed habitats that can be compared with other similar ecosystems that are still subject to human action (44).

To pick just one of those long-term research projects, the Lauvitel forests were last logged in 1922 and thus have been functioning since then without significant management interference (55). From 2006, dead wood had been inventoried on 32 permanent plots in the forest in a protocol where the living wood, standing dead wood and dead wood on the ground were measured (for the location of the permanent plots (see Fig. 4 in (56)). The regeneration area on each plot was also estimated as the area occupied by saplings. This data makes possible the characterisation of the forest stand and determine its dynamics, in particular, the cohabitation between the different phases of forest development, such as a regrowth phase occurring alongside trees in the process of collapse, or trees in full maturity. The importance of the dead wood was that it was seen as a potential indicator of biodiversity: cavity-nesting birds, bats, fungi, and insects. Thus, monitoring was underway in these plots on various species, particularly fungi and beetles, which would allow better understanding of the link between the volume of dead wood and the diversity of biological organisms. The observation was the forest of the Lauvitel integral reserve had a volume of dead wood three times higher when compared to managed forests in the Alps A priority during the next inventory would be to determine the rate of decomposition of the dead wood.

The colonisation and succession of life on Surtsey would be as natural as possible and, important from a scientific standpoint, would undergo minimal disturbances caused by man

Ten years ago, I wrote about an extraordinary challenge that James MacKinnon had put forward in his book The Once and Future World (57). He imagined an undiscovered island, a lost island, and then asked whether it would test our credulity that we would open it to exploitation, or would we imagine that today's enlightened society would see such an unspoiled place as inviolable? MacKinnon went through a series of choices of what could happen if we were to occupy the island. It was an allegorical attempt to foresee a new future for people and wild nature where humans were inseparable from the rest of life, a “world in which humanity can express all of its genius, and so too can nature”. What Mackinnon didn’t consider was whether wild nature would ever be possible to express all of its genius if, as he suggested, that wild nature be given only 12% of the land and sea around the island as “safeguarded” but without specifying what that safeguard would be. There would, of course, have been an undeniable safeguard if the decision had been made to have left the island entirely to wild nature.

Mackinnon may not have been aware of Surtsey, a volcanic mass that arose from the sea SE of Iceland back in 1963, as it does not appear in his book (58). Emerging on 15 November 1963, the island grew rapidly in size as multiple eruptions of volcanic ash and lava occurred until 5 June 1967 (see Ch. 2b, in (59)). By the end of the eruptions, Surtsey had grown to a size of 2.65km2. The total amount of eruptive material was estimated to be 1.1km3, about 70% of which was volcanic ash and 30% lava. The height of the island at that time was 175m above sea level, but as the depth of the sea before the eruption had been about 130m, then total height of the volcano was 305m. A substantial portion of the volcano exists under the sea by virtue of a mainly submarine ridge approximately 5.8 km long and oriented southwest-northeast. Measured from northwest to southeast, the volcano's maximum width is 2.9km and its base area encompasses some 13.2 km2. However, after erosion of the loose volcanic ash and lava by many harsh winter seas, the surface area of Surtsey decreased to 1.41km2 with a maximum width from west to east of 1.33 km and a maximum length from north to south of 1.80km. Given the fiery nature of its birth, the island was named after Surt, a fire giant in Norse mythology, so that Surtsey means Surt's island, since ey is “island” in Icelandic.

Scientists, including earth scientists and biologists, first stepped ashore on 16 December 1963. The research value was acknowledged by the scientific community after it became evident that Surtsey would prove lasting and so offered an exceptional opportunity to study the development of an oceanic volcano from its inception on the sea floor, through the formation of an island, to the new land's modification by hydrothermal processes, and abrasion in a coastal environment of strong wave activity. In addition, the island provided a unique opportunity to study the colonisation and succession of life on a sterile island surface. The Icelandic state took ownership (see pg. 87 in (59)) and by 1965, the island was protected by law, as it was put forward by the Nature Conservation Council of Iceland to become a nature reserve, being gazetted on 19 May 1965 under the Nature Conservation act of 1956 (see Appendix 1a in (59)). The purpose of the protection given in the designation was to ensure that the colonisation and succession of life on the island would be as natural as possible and, important from a scientific standpoint, would undergo minimal disturbances caused by man. The designation forbade anyone going ashore on the island, unless a permit had been issued by the Surtsey Research Committee, that Committee entrusted by the Nature Conservation Council with supervision of the island, including all scientific investigations. The protection of Surtsey was revised through a new Act on Nature Conservation 1971, the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture announced this revised protection in the Official Gazette (60). The latter added prohibition of the disruption of anything on the island; transporting there any animals, plants, seeds, or plant parts; leaving waste behind of any kind; and any shooting within 2km of the island. These prohibitions were obviously put in place to prevent any spurious contamination by human agency; the prohibition on shooting presumably so as not to interfere with any migration of birds to the island. Surtsey as a volcano then got protection as a natural formation under the Nature Conservation Act 1999 (see Article 53 in (61)).

Zoning in the Surtsey reserve

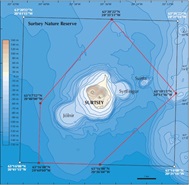

The most significant change to the protection of Surtsey was when it was decided to renew the protection so that it covered the entire volcano, above and below the sea down to the sea floor, and including the undersea islets Jólnir, Syrtlingur, and Surtla, together with a specified area of ocean around the island ((62) and see map therein). In effect, this designation of the nature reserve created a strictly protected core area of 33.7km2 with Surtsey and the undersea islands inside (red line on map) that was surrounded by a less-regulated buffer area of 31.9 km2 (black line on map). The passage of vessels was allowed in both zones. Along with the bans previously enacted for activities on land, diving around the island was also banned without permission for research purposes, along with fishing in the core area with gear that was dragged along the sea floor, such as bottom trawling, as well as the use of firearms. Fishing was allowed within the buffer zone, but construction, mining and the use of firearms were prohibited. In addition, a six-member Advisory Committee was to be set up with a range of representatives, and which would advise the Environment and Food Agency on matters of the nature reserve. An amendment to that designation in 2011 added a sentence that said that the Advisory Committee sets guidelines for good practices in the nature reserve, which are based on caution in dealing with the sensitive nature of the area (63). The original article on permitted access to the island was made clearer: unless as part of a research expedition, photography or filming would only get permission if accompanied by an employee of the reserve; any trips to Surtsey for specific works in the nature reserve would need permission, but permits would only be granted under exceptional circumstances during the breeding season (see later). When deciding on a permit, the Environment Agency would take into account the objectives of the protection cited in the renewed designation on the protection of flora, fauna and landforms. Given the strict protection of the core area of the reserve afforded by this renewed designation, it was classified under IUCN Category Ia in 2006 (see pg 87 in (59)).

To look at, Surtsey has two prominent crescent-shaped cones across the top third of the island, the crescent openings facing south east, and the two cones being composed of volcanic ash and palagonite tuff (a basaltic glass )(see pg. 16 (59)). The eastern cone, Austurbunki, rises to 155m and is marked by several small lava craters and fissures. The western cone, Vesturbunki, whose height is 141m, has large slump scars due to marine abrasion on its western side, where a 135m-high sea cliff has formed. The southern half of the island is a lava field that gently dips down to the sea to the south and east, whereas transported coastal sediments have mainly been deposited at the north end of the island, constructing a broad spit. Free from human interference, Surtsey has provided researchers with long-term information on the colonisation process of new land by plant and animal life. The Surtsey Research Society maintains a website full of information that covers the arrival of species on land, its geology, and the sea and shore, as well as Surtsey Research, a journal published by the Society (64).

Colonisation of Surtsey rapidly began

In the first spring after the formation of Surtsey, seeds and other plant parts were found washed up on the newly formed shore. The first higher plants discovered in the sandy shoreline of the northern part of the island were sea rocket (Cakile arctica) followed by sea sandwort (Honckenya peploides) sea lyme grass (Leymus arenarius) and oyster plant (Mertensia maritima). The seeds of these pioneer coastal species are large and float easily. Tolerating salt water, they probably originated from the sandy shores of Heimaey, an island 18km away, or the sand flats at Landeyjasandur on the south coast of Iceland, 32 km away (65,66). Wind dispersal was also important in plant colonisation, with the lighter seeds of dwarf willow (Salix herbacea) woolly willow (Salix lanata) tea-leaved willow (Salix phylicifolia) common dandelion (Taraxacum spp.) and the autumn hawkbit (Leontodon autumnalis) having established in this way. During 1965–2015, a total of 74 vascular plant species were found (65). Spores of ferns, mosses, lichens, horsetails, fungi and algae also found their way to the island by wind dispersal, including field horsetail (Equisetum arvense) common bladder fern (Crystopteris fragilis) the moss Racomitrium ericoides, and the lichen Stereocaulon vesuvianum (66-69). The total number of bryophytes increased from 43 to 59 between 2008 and 2018 (68) and 87 species of lichens have been found (67). It is birds, however, that have translocated the most plant species, with the estimate that 75% have been dispersed by birds, 15% by wind and 10% by the sea (66). Thus, some species of birds eat berries or fruits that contain seeds, which they then carry with them and expel as waste in new locations. In addition, seeds can stick to birds, or end up in their digestive tract when they eat their prey. Furthermore, birds carry materials for nest building, and these materials are most often plant materials. The dancing midge (Diameza zernyi) was the first insect discovered on Surtsey in May 1964, others following were mostly flying insects, but some were accidental species blown in on the wind, or floated on the sea surface (70). Of the 354 invertebrate species found on Surtsey, only 144 were regarded as permanent settlers. As the insect population, grew, it made Surtsey a more suitable place for birds other than seabirds to nest, such as the insect-eating meadow pipit (Anthus pratensis) wagtail (Motacilla alba) and snow bunting (Plectrophenax nivalis) (71). In 2003 eleven avian species bred on the island with a total of about 850 breeding pairs. After 2003 two more species started breeding, common puffin (Fratercula arctica) and raven (Corvus corax).

Once a dense seagull population had begun to form on Surtsey in 1984, numerous new plant and invertebrate species colonized the island in the following years, as the birds had a significant impact on plant growth and soil formation. While birds as migrants had been seen to visit the island as soon as it appeared, it wasn’t until 1970 that there was evidence of breeding, when two black guillemot (Cepphus grylle) nests and a fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) nest were discovered (71). Others followed over the next two decades, including Great Black-backed gull (Larus marinus) kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla) Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea) herring gull (Larus argentatus) Lesser Black-backed gull (Larus fuscus) and Glaucous Gull (Larus hyperboreus). The excreta and food scraps of this colony of breeding gulls, a transfer of nutrients from sea to land, as well as decomposing nest materials, resulted in plant growth and soil formation, giving rise to an expanding grassland vegetation developing on the southern part of the island where the seabirds mostly nested, the seeds of meadow buttercup (Ranunculus acris) smooth meadow grass (Poa pratensis) bering’s tufted hairgrass (Deschampsia beringensis) and northern dock (Rumex longifolius) being brought in by the gulls, while most parts of the island remained barren (72). There was to be another factor, though, influencing the trajectory of colonisation, and that was the arrival of seals in the early years, and their eventual breeding on the northern part of the island from 1983, and where a later patch of vegetation developed (72). There were few gulls nesting in this area, but a survey in 2019 showed 94 grey seals in the northern area, 62 were pups and 32 adults. Seal pups do not defecate during a fasting period after being weaned, but it is likely that their urine, and that from their mother, as well as from the release of the placenta and its fluids at birth, were the sources of nutrients that led to plant growth and soil formation there.

A compelling argument for recovery and reconnection

I have given only a glimpse of the remarkable appearance of species in and around Surtsey and the processes of transformation that they have brought about (for species lists up to 2007, see Appendices 2-9 in (59)) but without going into detail about the ebb and flow as pioneer plant species dwindled and were replaced by more dominant ones able to cope with the rising soil nutrients; that there were years when the Arctic tern did not return to breed on the island (71); and that the continuing erosion of the lava of the lowland areas by wave action as it sloughs into the sea will increasingly reduce the area that is amenable to nutrient enhancement, and may eventually leave just the inertness of the palagonite tuff of the cones, and which itself will erode at a much slower rate (see Fig. 2.24 in (59). These aside, Surtsey, along with Lauvitel integral reserve in France and the Swiss National Park, by virtue of the intent to exclude human agency, offers space to non-human species to live their natural lives, the intrinsic properties of inherent ecological processes, a self-will of existence (73). It can so easily be subverted, even in these closely controlled spaces, such as by inadvertence, or by deliberate intent. A mysterious growth had been found on Surtsey in 1969 that turned out to be a tomato plant and which had grown out of a pile of human faeces, a phenomenon often observed as tomato seeds pass through the digestive tract unscathed (74). The plant and faeces were bagged and removed from the island, the lesson learnt being a reinforcement of the stricture of preventing and removing all wastes. Later, in 1977, potatoes were found growing on the island. They could not have been washed ashore by the sea, and so they had to have been deliberately planted. It turned out that some mischief-seeking youths had rowed over from a nearby island and planted them.

If we are so inattentive to fostering unexploited locations where we may be observers only of the natural lives of wild nature, then there is the real risk that we won’t know what those natural lives are, as they are subverted by an enforced and exploitative coexistence with us, the most dangerous species. Further, we are greatly reducing the evolutionary potential of non-human species through extinctions, but more insidiously through fragmentation and loss of their unfettered living, and which blocks genetic flow between populations. Using a spatiotemporal approach, there is a recent projection of a loss in genetic diversity in 13,808 species due to depletions of natural living space and disconnection, with a short-term loss of 13–22% and long-term loss of 42–48% (75). The authors say that there is a time lag between the loss of living space and disconnection being then expressed in a decreasing genetic diversity so that the decrease will continue even if we protect all species and their current living spaces. They say this signals an urgent need to ambitiously recover and reconnect populations, so ensuring species’ long-term genetic protection. The scientific wilderness is thus more than just an academic pursuit, it is where we learn the absolute importance of the self-will of existence of wild nature. Observation of that self-will of existence is a compelling argument for its recovery and reconnection.

Mark Fisher 25 October 2024

(1) Wolf hunting controls relaxed in Switzerland, SWI 2 June 2023

https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/politics/wolf-hunting-controls-relaxed-in-switzerland/48561456

(2) Swiss government authorises shooting of 12 wolf packs, SWI 28 November 2023

https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/society/swiss-government-authorises-shooting-of-12-wolf-packs/49012996

(3) Wolf, Grossraubtiere in Graubünden, Kanton Graubünden

https://www.gr.ch/DE/institutionen/verwaltung/diem/ajf/grossraubtiere/Seiten/Aktuelle-Situation.aspx

(4) Kanton verfügt auf neuer gesetzlicher Grundlage weitere Wolfsabschüsse, Kanton Graubünden Medienmitteilungen 29 November 2023

https://www.gr.ch/DE/institutionen/verwaltung/diem/ajf/ueberuns/aktuelles/Seiten/202311291.aspx

(5) Switzerland’s December 2023 - January 2024 wolf cull. OPEN LETTER to Federal Councillor Albert Rösti and the Standing Committee of the Bern Convention

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1xeFrsSxEzdatHvcnhRgcf8SGj9hivEx-mEULBZBdG9E/edit

(6) Proaktive Wolfsregulation: Kanton Graubünden zieht positives Fazit. Kanton Graubünden Medienmitteilungen 5 February 2024

https://www.gr.ch/DE/Medien/Mitteilungen/MMStaka/2024/Seiten/2024020501.aspx

(7) Kanton reicht Sammelgesuch zur proaktiven Wolfsregulation ein, Kanton Graubünden Mitteilungen 15 August 2024

https://www.gr.ch/DE/Medien/Mitteilungen/MMStaka/2024/Seiten/2024081502.aspx

(8) Kanton verfügt Regulierungsmassnahmen bei Wölfen, Kanton Graubünden Mitteilungen 3 September 2024

https://www.gr.ch/DE/Medien/Mitteilungen/MMStaka/2024/Seiten/2024090302.aspx

(9) Abschuss des Wolfsrudels beim Nationalpark aus wissenschaftlicher Sicht nicht angezeigt, Forschungskommission des Schweizerischen Nationalparks (FOK-SNP) Medienmitteilung 20 September 2024

(10) Stellungnahme zur Entnahme des Wolfsrudels Fuorn beim Schweizerischen Nationalpark der Forschungskommission des Schweizerischen Nationalparks, der Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz 20. September 2024

(11) Kommission, Forschungskommission des Schweizerischen Nationalparks (FOK-SNP) Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Schweiz (SCNAT)

https://fok-snp.scnat.ch/de/portrait

(12) Facts and Figures, Basis and impressions, Swiss National Park

https://nationalpark.ch/en/about/national-park/

(13) Location, The Swiss National Park

https://nationalpark.ch/en/about/

(14) News 2024, Entwicklungen bezüglich Wolfsrudel Fuorn, Aktuelles von den grossen Beutegreifern, Schweizerischer Nationalpark

https://nationalpark.ch/flora-und-fauna/aktuelles-grosse-beutegreifer/

(15) Kanton verfügt Regulierungsmassnahmen bei Wölfen, Kanton Graubünden Mitteilungen 26 September 2024

https://www.gr.ch/DE/institutionen/verwaltung/diem/ajf/ueberuns/aktuelles/Seiten/202409251.aspx

(16) Stellungnahme des Schweizerischen Nationalparks zur Abschussverfügung für das Fuorn-Wolfsrudel, Zernez, 26. September 2024

(17) Federal Act on the Swiss National Park in the Canton of Graubünden of 19 December 1980 (Status as at 1 January 2017)

https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1981/236_236_236/en

(18) Fisher, M. (2016) ‘Ecological values of wilderness in Europe’, in K. Bastmeijer (ed.) Wilderness Protection in Europe: The Role of International, European and National Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 67–93

(19) Bissegger, W. (1914) Über die Gründung des schweizerischen Nationalparkes. Die Rede Dr. Bisseggers vom 25. März 1914 im Nationalrat. Unser Nationalpark und die ausserschweizerischen alpinen Reservationen. Neujahrsblatt Naturforschende Gesellschaft Zürich. Stück 130, 1928: 3-

https://www.ngzh.ch/media/njb/Neujahrsblatt_NGZH_1928.pdf

(20) Bundesbeschluss betreffend die Errichtung eines schweizerischen Nationalparkes im Unter-Engadin. (Vom 3. April 1914.)

https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/fga/1914/2_836_645_/de

(21) The research commission, Research basis, Swiss National Park

https://nationalpark.ch/en/research/basis/

(22) Research, Basis and impressions, Swiss National Park

https://nationalpark.ch/en/about/national-park/

(23) Schröter, C. (1920) “Der Werdegang des schweizerischen Nationalparks als Total-Reservation und die Organisation seiner wissenschaftlichen Untersuchung,” Ergebnisse der wissenschaftlichen untersuchung des Schweizerischen Nationalparks. Denkschriften der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 55: 2-8

https://www.parcs.ch/mmds/pdf_public/1666_schroeter-bandlv_abhi_1920.pdf

(23) Protection regulations, Swiss National Park

https://nationalpark.ch/en/protection-regulations/

(24) BR 498.200 - Verordnung über den Schutz des Schweizerischen Nationalparks (Nationalparkordnung) vom 23.02.1983, in Kraft seit: 01.04.1983. Kanton Graubünden

https://www.gr-lex.gr.ch/app/de/texts_of_law/498.200/versions/2411

(25) Wildnis als Auftrag, Grundlagen & Impressionen, Schweizerische Nationalpark

https://nationalpark.ch/about/nationalpark/#wildnis

(26) Besonderheiten des Nationalparks, Grundlagen & Impressionen, Schweizerische Nationalpark

https://nationalpark.ch/about/nationalpark/#besonderheiten

(27) Dudley, N. (Editor) (2008). Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. x + 86pp. WITH Stolton, S., P. Shadie and N. Dudley (2013). IUCN WCPA Best Practice Guidance on Recognising Protected Areas and Assigning Management Categories and Governance Types, Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 21, Gland, Switzerland: IUCN

https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/PAG-021.pdf

(28) Wolfsrudel im Schweizerischen Nationalpark nachgewiesen, Schweizerische Nationalpark 13 September 2023

https://nationalpark.ch/medianews/wolfsrudel-nationalpark/

(29) Wolfsnachwuchs im Schweizerischen Nationalpark, Schweizerische Nationalpark Medienmitteilung vom 2 August 2024

https://nationalpark.ch/medianews/wolfsnachwuchs-im-schweizerischen-nationalpark/

(30) Wolf - Einfluss auf die Nahrungsnetze. Forschungsprojekt. Schweizerischer Nationalpark - Wolfsmonitoring im Schweizerischen Nationalpark, Netzwerk Schweizer Pärke

https://www.parks.swiss/de/karte.php?offer=40278

(31) Wer ist CHWOLF

https://chwolf.org/ueber-uns/wer-ist-chwolf

(32) New wolf culling policy, Switzerland 2023/3, Monitoring, Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, Council of Europe

https://www.coe.int/en/web/bern-convention/-/new-wolf-culling-policy

(33) 2023/3: Switzerland: New wolf culling policy, Complaints on stand-by. Meeting of the Bureau 10-12 September 2024 ((Strasbourg)) CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS Standing Committee 44th meeting, Council of Europe. MEETING REPORT 9th October 2024 T-PVS(2024)11

https://rm.coe.int/tpvs11e-2024-bureau-meeting-10-12-september-2755-8761-8314-1/1680b1ea91

(34) 2023/03: Switzerland: New wolf culling policy. 6.2. Possible Files, DRAFT AGENDA, Standing Committee 44th meeting Strasbourg, 2-6 December 202, CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS, Council of Europe

https://rm.coe.int/agenda13e-annotated-2024-44th-standing-committee-draft-rev-2777-7158-5/1680b25e8e

(35) An axis of naturalness for treescapes, Self-willed land November 2020

www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/axis_natural.htm

(36) Arrêté du 23 février 2007 arrêtant les principes fondamentaux applicables à l'ensemble des parcs nationaux, Legifrance, République Française

https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000000274760

(37) Décret n° 2021-1611 du 10 décembre 2021 portant classement de la réserve intégrale forestière d'Arc-Châteauvillain dans le cœur du parc national de forêts

https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000044469145

(38) FR3500004 - Réserve intégrale d'Arc-Châteauvillain - Réserve intégrale de parc national, Inventaire national du patrimoine naturel

https://inpn.mnhn.fr/espace/protege/FR3500004

(39) Fisher, M., Carver, S., Kun, Z., McMorran, R., Arrell, K., Mitchell, G., & Kun, S. (2010). Review of status and conservation of wild land in Europe. Wildland Research Institute.

http://www.self-willed-land.org.uk/rep_res/SCOTTISH_WILDLAND_WRI.pdf

(40) Parc national des Ecrins

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/

(41) Parc national de Port-Cros

https://www.portcros-parcnational.fr/fr

(42) Loi n°60-708 du 22 juillet 1960 relative à la création de parcs nationaux, Legifrance, République Française

https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000000512209/2020-10-28/

(43) Section 4: Réserves intégrales (Article L331-16) Chapitre I: Parc nationaux, Titre III: Parcs et reserves, Livre III: Espaces naturels, Code de l'environnement, Legifrance, République Française

https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/section_lc/LEGITEXT000006074220/LEGISCTA000006176508/

(44) Réserve intégrale du Lauvitel : un outil scientifique

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/thematique/reserve-integrale-du-lauvitel

(45) Plan de gestion de la réserve intégrale de Lauvitel 2012-2025, Parc national des Ecrins

(46) Le parc national des Écrins en quelques dates, Parc national des Ecrins

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/parc-national-ecrins-quelques-dates

(47) La réserve intégrale du Lauvitel, c’est quoi? Le parc national et sa réglementation, Foire aux questions, Parc national des Ecrins

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/foire-aux-questions

(48) Décret n°95-705 du 9 mai 1995 portant création de la réserve intégrale de Lauvitel dans le Parc national des Ecrins, Legifrance, République Française

https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000000168541/2021-06-29

(49) FR3500001 – Lauvitel, Réserve intégrale de parc national, Inventaire national du patrimoine naturel

https://inpn.mnhn.fr/espace/protege/FR3500001

(50) ATBI du Lauvitel, vers un inventaire général de la biodiversité, Parc national des Ecrins

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/atbi-lauvitel-inventaire-general-biodiversite

(51) Oiseaux, mammifères et poisons, Parc national des Ecrins

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/oiseaux-mammiferes-poissons

(52) Flore vasculaire, Parc national des Ecrins

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/flore-vasculaire

(53) Lichens et champignons associés, Parc national des Ecrins

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/lichens-champignons-associes

(54) Champignons, Parc national des Ecrins

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/champignons

(55) L'inventaire forestier de la réserve intégrale, Parc national des Ecrins

https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/inventaire-forestier-reserve-integrale

(56) Château, J. (2018) Évolution du peuplement et du bois mort dans un contexte de forêt subnaturelle, en réserve intégrale de Lauvitel. Mémoire de fin d’étude (2 avril – 31 août 2018, Agrosup Dijon - Institut national supérieur des sciences agronomiques, de l'alimentation et de l'environnement, Parc national des Ecrins

(57) The challenge of Lost Island - making ourselves wilder, Self-willed land September 2014

www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/lost_island.htm

(58) MacKinnon, J.B. (2013) The Once and Future World:Nature As It Was, As It Is, As It Could Be. Houghton Mifflin

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=1RyqAAAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

(59) Snorri Baldursson and Álfheiður Ingadóttir (eds.) 2007. Nomination of Surtsey for the UNESCO World Heritage List. Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavík 2007

https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1267.pdf

(60) Auglýsing um friðlýsingu Surtseyjar, nr. 122/1974, 3 April 1974

https://urlausnir.is/pdf_saekja.php?pdf_tegund=skannad&pdf_skjal=209669

(61) Act on Nature Conservation, No. 44/1999, March 1999

https://www.ust.is/library/Skrar/Atvinnulif/Log/Enska/The_Nature_Conservation_Act.pdf

(62) Nr. 50 27. janúar 2006 AUGLÝSING um friðland í Surtsey.

https://ust.is/library/Skrar/Einstaklingar/Nattura/Fridlysingar/B_nr_50_2006.pdf

(63) AUGLÝSING um breytingu á auglýsingu nr. 50/2006 um friðland í Surtsey. Nr. 468 31. janúar 2011

https://ust.is/library/Skrar/Einstaklingar/Nattura/Fridlysingar/Surtsey,%20468_2011.pdf

(64) Surtsey, The Surtsey Research Society

(65) Magnússon, S. H., Wasowicz, P., & Magnússon, B. (2022). Vascular plant colonisation, distribution and vegetation development on Surtsey during 1965–2015. Surtsey Research 15: 9-29

https://surtsey.is/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Surtsey-2022_15_2_Vascular-plant-colonisation_9-29.pdf

(66) Magnússon, B., Magnússon, S. H., Ólafsson, E., & Sigurdsson, B. D. (2014) Plant colonization, succession and ecosystem development on Surtsey with reference to neighbouring islands. Biogeoscience 11(19): 5521-5537

https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/11/5521/2014/bg-11-5521-2014.pdf

(67) Kristinsson, H. & Heiðmarsson, S. (2009). Colonization of lichens on Surtsey 1970–2006. Surtsey Research 12: 81-104

https://surtsey.is/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2009-XII_081-104_Colonization-hi_03.pdf

(68) Ingimundardóttir, G. V., Weibull, H., & Cronberg, N. (2014) Bryophyte colonization history of the virgin volcanic island Surtsey, Iceland. Biogeosciences, 11(16): 4415-4427

https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/11/4415/2014/bg-11-4415-2014.pdf

(69) Ingimundardóttir, G. V., Cronberg, N., & Magnusson, B. (2022) Bryophytes of Surtsey, Iceland: Latest developments and a glimpse of the future. Surtsey Research, 15: 61-87

(70) Ólafsson, E., & Ingimarsdottir, M. (2009) The land-invertebrate fauna on Surtsey during 2002–2006. Surtsey Research 12: 113-128.

https://surtsey.is/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2009-XII_113-128_TheLand-inv-hi_05.pdf

(71) Petersen, Æ. (2009). Formation of a bird community on a new island, Surtsey, Iceland. Surtsey Research, 12: 133-148

https://surtsey.is/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2009-XII_133-148_Formation-hi_07.pdf

(72) Magnússon, B., Gudmundsson, G. A., Metúsalemsson, S. & Granquist, S. M. (2020). Seabirds and seals as drivers of plant succession on Surtsey. Surtsey Research 14: 115-130

(73) A natural life – the self-will of existence, Self-willed land Aug 2024

http://www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/intrinsic.htm

(74) The Tomato Plant Versus the Volcano, Dan Lewis, Now I Know 27 September 2018

https://nowiknow.com/the-tomato-plant-versus-the-volcano/

(75) Mualim, K.S., Spence, J.P., Weiss, C.L., Oliver Selmoni, O., Lin, M. and Exposito-Alonso, M (2024) Genetic diversity loss in the Anthropocene will continue long after habitat destruction. bioRxiv 2024.10.21.619096

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.10.21.619096v1.full.pdf

url:www.self-willed-land.org.uk/articles/scientific_wilderness.htm

www.self-willed-land.org.uk mark.fisher@self-willed-land.org.uk